The historical truth behind iron bars

Memory is sacred, lessons are eternal

May 9 is widely celebrated in our country as the Day of Remembrance and Honor. On this day, we remember hundreds of thousands of our compatriots who lost their lives in World War II and pay tribute to the heroes who returned safely from the battlefields. We also honor the memory of those who were unjustly accused and suffered under the cruel repressions of a totalitarian regime and lost their lives in distant lands, longing for their homeland.

During the Soviet era, all the republics—united under colonial rule—endured various forms of repression, the humiliation of human dignity, and the brutal suppression of any desire for freedom or independence. In Uzbekistan, thousands of intellectuals, prominent statesmen and politicians, scientists, artists, religious scholars, members of the military and judicial systems, as well as their families, also fell victim to political persecution.

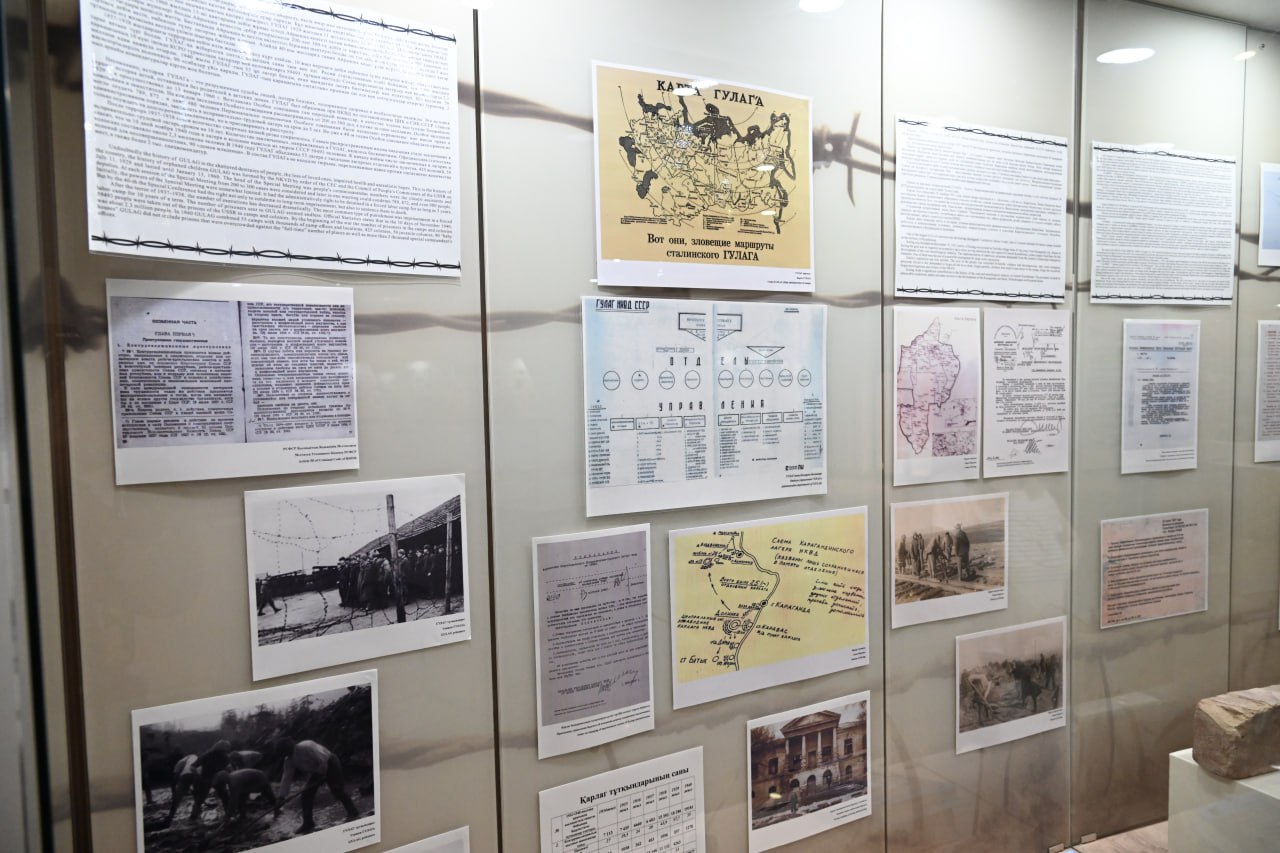

The number of prisoners was so great that the network of penal institutions stretched across a vast territory, from the remote reaches of Siberia to the deserts of Kazakhstan. Penal institutions such as KarLag (Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp) and ALZHIR (Akmola Camp for Wives of Traitors to the Motherland), located in the neighboring republic, became places where countless innocent lives were shattered and subjected to unimaginable suffering. Among those unjustly imprisoned and stripped of their basic human rights were many Uzbek intellectuals, along with their family members and loved ones.

We must never forget this chapter of our history. The younger generation must know it, study it thoroughly, and draw the right conclusions. In this regard, the decree issued by President Shavkat Mirziyoyev on July 19, 2024 — “On expanding efforts to study and promote the lives and legacies of our compatriots who fell victim to political repression and to preserve their memory” — serves to strengthen our independence in all its dimensions, to recover the overlooked pages of our history and examine them through a scholarly lens. Based on this foundation, it also aims to deepen our compatriotsʼ—especially the younger generationʼs—sense of responsibility and civic engagement toward the fate and future of the Motherland, and to educate them in the spirit of valuing the peaceful, free, and independent life we enjoy today.

Memory is not only about the past but also a moral pillar that builds the future with justice and vigilance. During our editorial staffʼs business trip to the KarLag and ALZHIR museums in Kazakhstan, the focus was not only on revisiting history but also on uncovering the enduring significance of historical memory and the lessons it offers for today.

When documents speak

Amid Astanaʼs modern skyline, towering skyscrapers, and peaceful atmosphere, the painful memories preserved in some corners of Kazakhstanʼs history feel all the more poignant. The KarLag and ALZHIR museums are places that reflect these sorrowful memories.

KarLag, located near the city of Karaganda, was one of the largest labor camp systems of its kind, sprawling across a territory comparable in size to modern-day France. It is remembered for its grim legacy and is recognized as the most prominent symbol of political repression in Central Asia. During the Soviet era, thousands of innocent people were imprisoned, tortured, and even killed within its confines. ALZHIR, on the other hand, was a prison camp designated exclusively for women, specifically, the wives and mothers of men labeled “enemies of the people.” These women were imprisoned and separated from their children solely because of their family ties.

According to Nurlan Dulatbekov, Rector of E.A. Buketov Karaganda University, Corresponding Member of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Doctor of Legal Sciences, Professor, these museums serve to preserve history not only in documents but also in human hearts. They speak the truth of life, reminding us of dark days, unforgivable mistakes, and human tragedies. These museums urge the current generation not to forget the past and not to repeat its errors. They serve as a bridge that, through memory and suffering, leads to justice and enlightenment.

“The mass political repressions of the first half of the 20th century entered human history as a horrific example of a totalitarian regime turning against its own people,” emphasizes Dulatbekov. “After the collapse of the Soviet Union, nations and states began to revisit their histories and seek to understand the consequences of this bloody terror. For many years, documents related to the KarLag were kept under strict secrecy. Once the archives were opened, numerous witnesses began sharing their memories with the public. These historical revelations did more than expose the grim chapters of political repression under the authoritarian regime — they also gave rise to new academic principles and scholarly interpretations. KarLag prisoners included intellectuals and prominent figures who had made significant contributions to the culture and economy not only of Kazakhstan but of all former Soviet republics.”

Each exhibit tells the story of an innocent life lost

A visit to the KarLag and ALZHIR museums is far more than a simple tour — it is a profound emotional journey into history. Prison cells, fabricated trials, letters soaked in sorrow, and lives confined behind iron bars — every exhibit tells the harrowing story of an innocent victimʼs fate.

The dark walls of KarLag, its cold prison cells, and the tools once used by prisoners condemned to hard labor — all of these artifacts offer a deeper understanding of how human dignity, freedom, and justice were brutally violated.

“The Museum of Political Repression Victimsʼ Memory in Dolinka village (KarLag Museum) was established in 2001 to research and preserve KarLag historical monuments and to perpetuate the memory of victims of forced labor camps located in Kazakhstan,“ says museum employee Elena Pistina. “Today, the museum is located in the former administrative building of KarLag, built between 1933 and 1935 by thousands of prisoners. Visitors are invited to explore 20 exhibition halls spread across two floors, featuring topics such as “Famine in Kazakhstan,” “The History of KarLagʻs Establishment,” “Economic Activities of KarLag,” “Women and Children,” and “The Deportation of Nations,” among others.

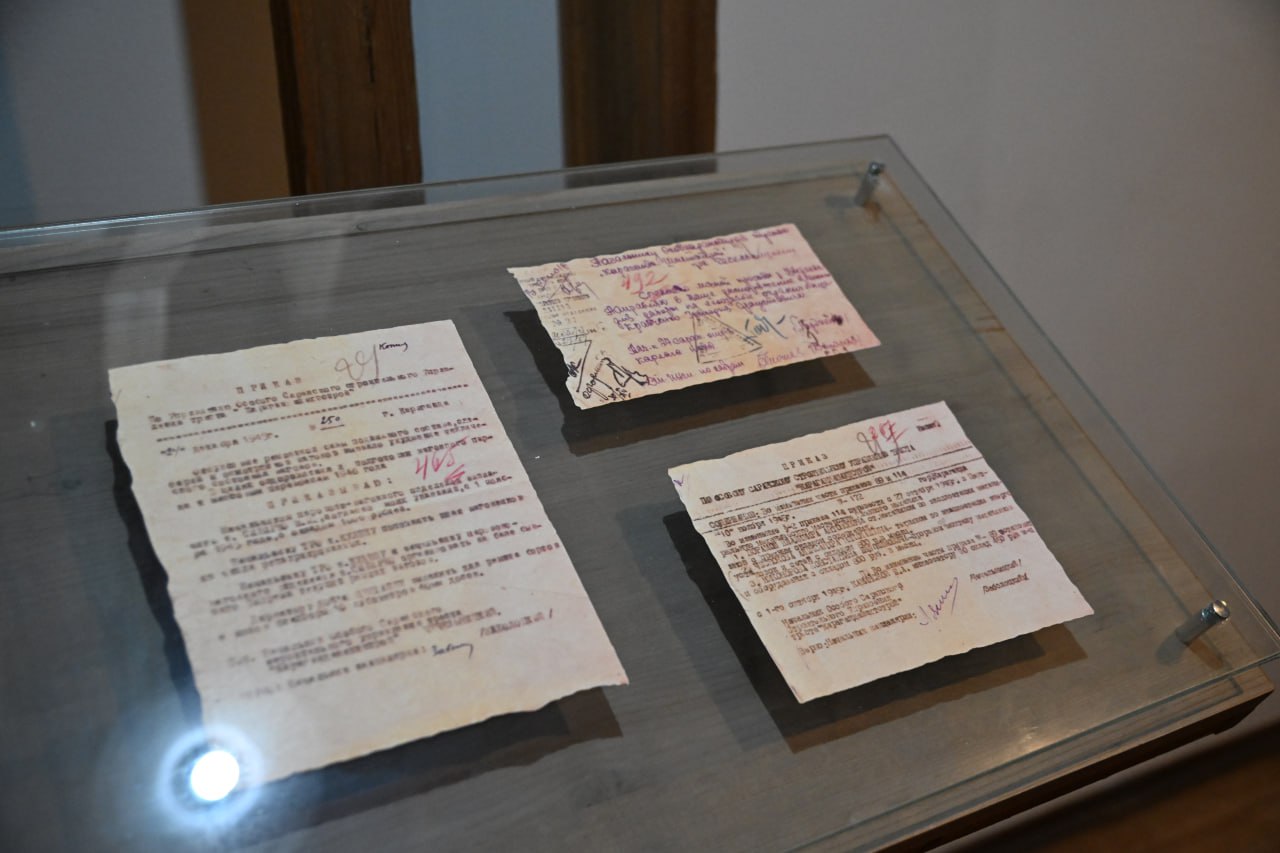

The permanent exhibitions of the museum include archival materials on the history of political persecution, letters, photographs, personal files of prisoners, and tools and household items found during expeditions. The collection also includes artworks created by camp prisoners.

One notable section is the reconstructed basement that replicates the investigation wing, featuring prison cells for men and women, interrogation rooms, and torture chambers. It also displays the conditions in which prisoners were held, the process of interrogations, and how case files were documented. The installation includes realistic statues of victims of repression, guards, and investigators, drawing visitors into the haunting atmosphere of the era and prompting reflection and lessons from history.

The museum also engages in scientific and educational activities. The Scientific Research Center on the History of Political Repression presents works prepared by scientists based on archival materials.

The museum regularly organizes meetings with former KarLag prisoners and descendants of repression victims. Conferences, meetings, and seminars are held on the Day of Remembrance for Victims of Political Repression and Famine. Scenes from the lives of KarLag prisoners are vividly brought to life in the exhibition halls. The museum holds periodic exhibitions throughout the year, showcasing items from its own collection and private collections. The museumʼs collection contains approximately 15,000 exhibits, more than 6,000 are original historical artifacts. A sufficiently rich and diverse range of materials has been collected for the main collection.

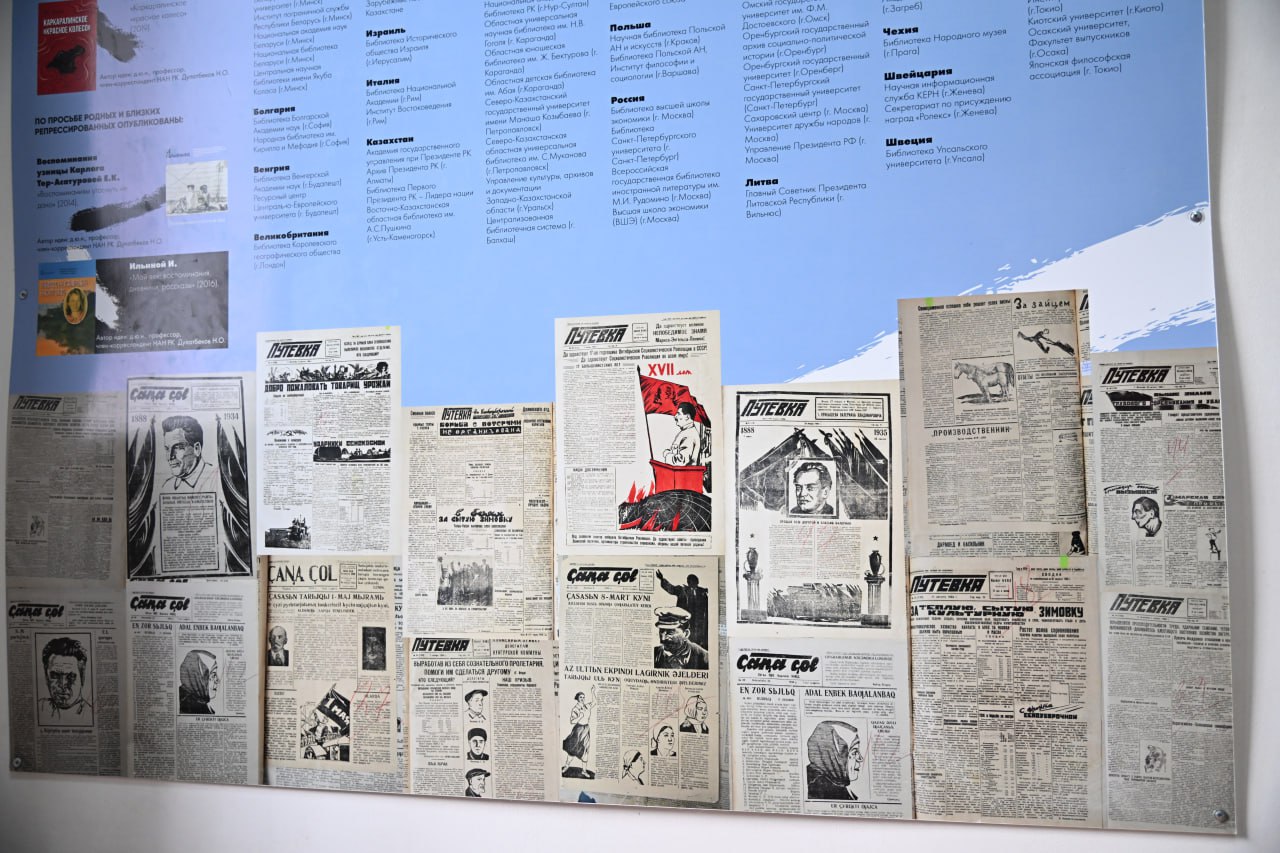

Photographs and documents hold a special place in the museumʼs exhibitions, as they offer firsthand testimony about life inside the camps. Among its rarest items are the 1931 issue of the Putyovka newspaper (“Путёвка”), the 1932 issue of Jana Jol newspaper published in Kazakh using the Latin alphabet, and various prisoner diaries.

The museum also houses unique works by deported artists P.I. Rechensky, L.P. Andreyuk, and L.E. Hamburger, everyday items of the Kazakh people from the 1920s-1930s, sewing products made by prisoners, musical instruments from that period, equipment produced by prisoners in the repair and mechanical factory, personal belongings of deported peoples, and many other rare exhibits.

The number of visitors to the museum is increasing year by year. It attracts not only citizens of Kazakhstan but also visitors from neighboring countries and around the world.

Women with shattered destinies

At the ALZHIR Museum, the bitter fate of women deprived of love, motherhood, and life itself is painfully revealed. More than 18,000 women were imprisoned at this tragic site during various years, not for crimes they committed, but simply because their husbands or children had been labeled “enemies of the people.“ These women were innocent.

Among those imprisoned were family members of many prominent state and political figures of the time. For example, women from the family of Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was executed on charges of treason; the wife of writer Boris Pilnyak, Kira Andronikashvili; the mother of writer Yuri Trifonov, Yevgenia Lure; the wife of statesman Turar Ryskulov, Aziza Ryskulova-Isengulova; the wife of writer Beimbet Mailin, Gulzhamal Mailina; as well as the mothers of Bulat Okudzhava and Maya Plisetskaya—all endured the suffering of ALZHIR.

Even young, innocent children were held captive in this prison, too young to understand the reasons for their suffering. It is very difficult to hold back tears when seeing childrenʼs shoes preserved in the museum, statues depicting young prisoners, and writings about them.

According to museum staff member Gauhar Rizaliyeva, the ALZHIR museum and memorial complex is a historical site dedicated to the memory of victims of political repression during the totalitarian regime, clearly demonstrating what blindly conducted policies of oppression can lead to.

The museum building is shaped like a truncated cone, resembling a box that holds sorrow. It has no windows, and light enters only from above, as if lifting a mysterious veil. Visitors enter the museum via an underground passage lined with illustrations depicting key events from the era of political repression.

The museum-memorial complex comprises several components. The “Stalin Carriage” or “Red Wagon” was used to transport detainees and deportees. The “Arch of Sorrow” sculpture carries deep symbolism, portraying a woman in mourning for her executed husband and lost children. Visitors passing beneath the arch are invited to bow their heads in respect for the victims of these tragic years.

Foreign embassies have established memorials around the ALZHIR complex to eternally commemorate the memory of women from 62 nationalities.

In addition, the composition “Despair and Helplessness” conveys the loss of paths to freedom, expressing a deep sense of powerlessness and hopelessness. The composition “Struggle and Hope” symbolizes a woman longing for freedom, striving to break free from her cage. In her pursuit, she turns to poetry, beauty, and creativity. The stele titled “Tears” is dedicated to all those who endured the horrors of the camps. It depicts a map of the GULAG system along with the names of 11 camps that were part of the KarLag network in Kazakhstan. The tears of women and children behind barbed wire serve as a tragic symbol of the fate of ALZHER prisoners and their descendants.

The Barrack was the living space for women labeled as “socially dangerous and prone to anti-Soviet behavior.” One of the key exhibits is a diorama depicting the scene of children being taken away from the ALZHIR prisoners. The Alash Garden, spanning 1.5 hectares, was originally planted by female prisoners and is now being restored. The Wall of Remembrance displays the names of more than 7,000 women who served sentences at ALZHIR.

A visit to this museum is not just a visual experience — it is one deeply felt. This is a place that stirs the conscience and awakens the soul.

Conversation with the past and responsibility for the future

Every step taken within the KarLag and ALZHIR museums is a conversation with the past; every tear shed is a lesson for the future. These places serve as solemn reminders that peace and freedom were not attained easily — countless lives and destinies were sacrificed for the happy life we live today.

Today, Uzbekistan is turning to its history and uncovering the dark pages of totalitarianism. Special attention is being given to preserving the memory of our ancestors who fought for the independence, freedom, peace, and prosperity of our country—those who sacrificed their lives and were repressed during the former Soviet Union. Their lives, work, and legacy are being studied and promoted with great care.

It is especially noteworthy that between 2021 and 2024, the Supreme Court of the Republic of Uzbekistan officially rehabilitated the names of over 1,200 victims of political repression.

The State Museum of the Memory of Victims of Repression, its regional branches, and the State Museum of the Jadid Legacy are continuously enriched with thematic materials, artifacts, documents, and related exhibits.

Magnificent monuments and museums dedicated to the memory of our great enlightened ancestors, such as Mahmudkhoja Behbudiy, Abdulla Avloniy, Ishakhon Ibrat, Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulhamid Cholpon, and Abdulla Qodiriy, have been built, and schools bearing their names have also been established to preserve their legacy. Scientific research works, artistic and documentary works aimed at identifying unjustly persecuted compatriots and publicizing their contributions are actively underway.

Indeed, understanding the history of oppression is of critical importance. A generation that recognizes the tragic crimes of the totalitarian regime and the suffering it inflicted on entire nations will truly value peace and freedom. A nation that turns to the past and draws the right conclusions will know how to shape its present and future. It will stand up for peace, unity, independence, and national dignity — and confidently stride toward a prosperous and happy life.

Nurlan USMONOV

(“Xalq soʻzi”).

Tashkent — Astana — Karaganda — Tashkent.

Recommended

Popular news

- Saida Mirziyoyeva speaks at Global Forum in Abu Dhabi

- New Uzbekistan and Peace Diplomacy

- Youth exhibition “Chinese Art inUzbekistan” opens in Fergana

- Uzbek national on Interpol wanted list extradited from the UAE

- “Not Shakespeare, but his English is getting better,” Guardiola says of Khusanov

- Uzbek President awarded honorary titles of Doctor and Professor by a leading university of Pakistan

Comments

No comment yet. Maybe you comment?

Enter to comment